In 1993, two years after the U.S. women’s national team won its first World Cup, 25-year-old defender Joy Fawcett approached then-head coach Anson Dorrance and told him she wanted to have kids. Not only that, she wanted to bring them on the road.

“I didn’t want to have them and then have them be left at home when I traveled,” she says 30 years later.

Fawcett’s desire to become a mother was greater than anything, and she was prepared to quit soccer if her dream became an issue. But Dorrance, who coached the USWNT from 1986-1994, “didn’t even blink an eye,” Fawcett says.

“And that’s just kind of how it happened,” she continues. “It went from there.”

Fawcett gave birth to daughter Katelyn in May 1994, making her the first U.S. soccer mom in the World Cup era (Joan Dunlap had previously earned four national team caps as a mom in 1986). Over the next 10 years, Fawcett would have two more kids while playing in three more World Cups and two Olympics. She even played every minute of the 1995 World Cup one year after having a baby.

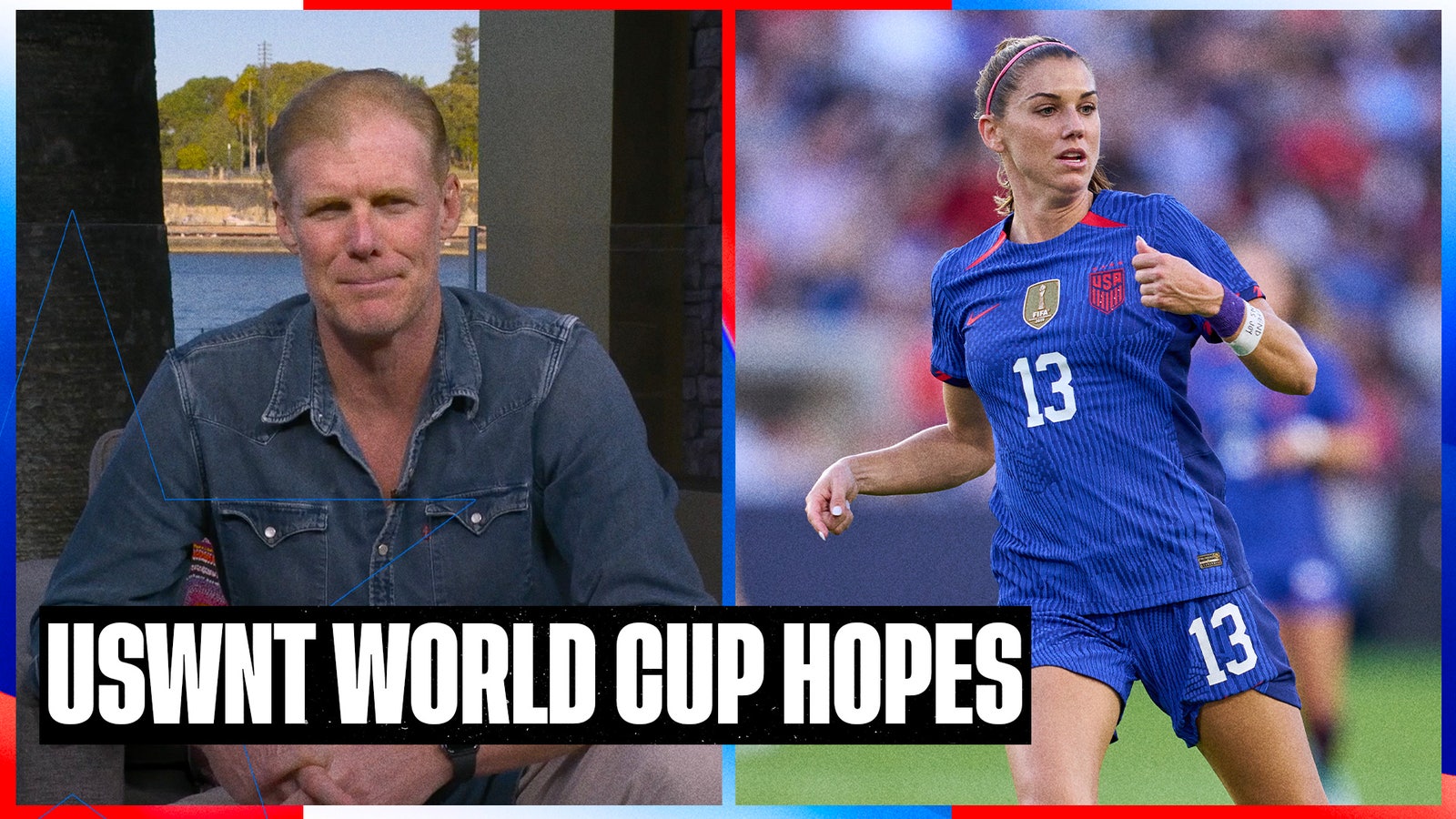

As the 2023 version of the USWNT prepares for this summer’s World Cup in Australia and New Zealand — the Americans’ first match against Vietnam is Friday (9 p.m. ET on FOX and the FOX Sports app) — it does so with three mothers on the roster, matching a previous record set in 2015.

Alex Morgan, Crystal Dunn and Julie Ertz will each play an integral role in helping this squad try to make history by winning a fifth title and third in a row.

And while Fawcett didn’t realize the magnitude at the time, all the breakdowns and tough times and running sprints a little too deep into pregnancy (to which her doctor eventually said, “Oh gosh, you have to stop that!”) paved the way for future generations of soccer moms.

“I’m just really grateful for the women before me that fought for mom athletes,” Morgan says. “Joy Fawcett was the OG in that she had way less resources and support and was able to somehow become a world champion and do so many great things to create the legacy she has today.”

Here’s the story of the mothers that blazed the trail for this year’s trio of moms and others to come.

*** *** ***

Being the “OG” meant Fawcett had no model to follow. She had to figure everything out herself, which included but was not limited to finding a nanny (often her own mom, husband or a high school kid), paying for a nanny (including flights, hotel rooms and meals), “and carrying 10 bags plus a car seat.”

She had to bunk up with teammates in hotels, playing into her fear that by bringing a child into training camp and staying up with them all night would negatively impact another player’s game or team chemistry. “I didn’t want to impose myself on anyone,” Fawcett says. Eventually, she’d get her own room, but had to pay for that, too.

Carla Overbeck, who later became the second “OG” mom in 1997, says players pooled money from their stipends and per diems to help pay for Fawcett’s various expenses. Fawcett might have been the only USWNT mom for a period of time, but players had the foresight to understand she wouldn’t be the last.

“In the early days, we all just knew Joy was really important to the team, so we’d make a fund and help her with that,” Overbeck says.

[USWNT’s secret to sustained success? A mentorship circle that keeps paying it forward]

There was no blueprint when it came to recovery after childbirth and knowing how and when to return to the field, either. Fawcett took cues from magazines and followed La Leche League — an organization that organizes advocacy, education and training for breastfeeding.

One time when she was training for the Olympics Sports Festival, the dorm the team stayed at didn’t allow children, so she lived with a volunteer who swooped in after hearing about the situation. Fawcett was also breastfeeding at the time and got in trouble for feeding Katey in the cafeteria “because people complained,” Fawcett says.

And it’s not like Fawcett had maternity leave. Two weeks after having Katey, she visited her teammates at training near her home in Southern California, just hoping to introduce everyone to her baby. But when Dorrance saw her, he said she looked fine and should “come play tomorrow.”

So, she did.

“I came back quickly and most of it was insecurity for my position,” Fawcett says. “I was too scared to say no, so I dragged my mom to the field and just started playing. It was fine, but I had no clue as to why I shouldn’t be [playing] then with your loose joints or whatever.”

Players today don’t feel quite as rushed, though that’s not to say they don’t feel pressure.

Morgan made the 2021 Tokyo Olympics roster a year after having her daughter Charlie, but then didn’t get called back up for eight months. Dunn came back less than four months after having son Marcel — and scored a decisive goal to send the eventual NWSL champion Portland Thorns to the 2022 title game. And Ertz made a surprise return to the USWNT in April, about eight months after having son Madden, and worked her way into making her third straight World Cup squad.

But it hasn’t been an easy path here.

Fawcett remembers a time when the team was living in Florida for training camp before the 1995 World Cup. She became overwhelmed when there were only three days to find daycare for Katey. She “just started bawling” and told coach Tony DiCicco she couldn’t handle it.

“I was like, ‘Oh my God, I just dropped my daughter off with strangers, and I have no clue who they are,'” Fawcett says. “Tony was like, ‘Take all the time you need, figure it out and then come out when you’re ready.’ I was like, OK, deep breaths and I kept practicing. Having someone say they get it and be supportive and not have any repercussions was huge.”

And oh, by the way, she also still needed to have a separate full-time job to make ends meet because back then USWNT players didn’t have health insurance and were decades away from achieving equal pay. Fawcett coached at UCLA from 1993-97 in addition to playing at the highest level and being a parent.

Feeling overburdened, she ended up leaving coaching after having her second daughter Carli in 1997, but not before talking to the national team sports psychologist who “helped talk me off the ledge. She said, ‘You’re fine. You can do it.'”

Around this same time, Overbeck had her son, Jackson. Now there were two mothers on the USWNT with a total of three kids. Overbeck, the team captain, knew she would be OK because the coaching staff and players had been helpful to Fawcett. Her greatest worry was not being able to get back to peak performance after childbirth because “being fit was what I brought to the team.” She would run on the treadmill throughout her pregnancy “holding my belly” and was doing stadium stairs at Duke the day her water broke.

Overbeck’s doctor said “don’t overdo it” but everybody’s version of that is different. She saw Fawcett do it and knew she could, too.

“I mean, Joy is a machine,” Overbeck says. “She was fit, she had the baby and came out to camp a couple weeks later and jumped in with us. If I had to fund my husband or mom coming to be the nanny, then that’s what we would do.”

Leading up to the 1999 World Cup and 2000 Olympics, the USWNT put a more stable agreement together and asked the U.S. Soccer Federation to formally help. It began paying for childcare so players could keep their kids nearby.

“We, as women, wanted our children with us,” Overbeck says. “That was something the Federation never broached before, and they were willing to listen and help make our jobs easier so we could continue to be on the team with our children.”

Since then, support has only grown. In the most recent collective bargaining agreement, for example, players receive benefits that allow them to “continue to be paid an agreed-upon amount up to a maximum of six months” after pregnancy, per U.S. Soccer. It also became mandatory that they be invited into two training camps once they are medically cleared after giving birth.

While Fawcett and Overbeck were figuring things out as they went, players from other countries looked to them for guidance. Overbeck remembers being at banquets after major tournaments or friendlies when they’d be able to mingle with other teams from around the world. The Chinese players would always find Overbeck and extend their arms as a way to communicate that they wanted to hold Jackson.

“We could connect through our kids,” Overbeck says. “Because here you were rivals on the field, then you’d show up at events, and they would just want to hold your baby. And you don’t realize it until maybe you’re removed from it that the Swedish girls, Norwegians, Germans … so many players were thinking about starting a family, so they’d reach out to us like, ‘How did you do it with your federation? How did you get support? Was the coaching staff on board? Did you get back to peak performance?’

“I felt the U.S. did it before it was really done. You felt like you were part of their growth just like equal pay. We were just helping women live out their dream of playing soccer and having kids.”

*** *** ***

Having children around the national team has always been positive. From Easter egg hunts to playing hide-and-go-seek outside team meeting rooms, “it gives the environment a breath of fresh air,” Morgan tells FOX Sports.

“It humanizes people in a way that you don’t see in camp,” Morgan continues. “We live in this pressure-cooker professional environment, and you need to take time to have that balance.”

The team also can help share the load. Overbeck remembers the time Mia Hamm tried to help Jackson learn how to walk in a team hotel.

“We were in the hallway, and I would kind of guide him stepping toward Mia, and she would be acting goofy on the other end,” Overbeck says. “He started to fall and hit his face on the ground. Mia was like, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m so sorry!’ He got a bloody nose and she felt terrible. I gave her a hard time like, ‘You didn’t even catch him! Way to go!’ I said Mia gave him his first bloody nose. And, of course, I was kidding.”

[Alex’s Morgan father, the ultimate soccer dad: ‘He’s literally at everything’]

Overbeck lived with Julie Foudy and Kristine Lilly when they were in residency in Florida for training camp before the 1999 World Cup and 2000 Olympics, and they could always tell when she was having a tough day. So they’d take Jackson off her hands and go to the playground so she could have a break and “get a second to breathe.”

Fawcett had the same experience, but with Shannon MacMillan. Players were always willing to help out, and it was never a burden.

That tag-team effort remains today. Players say goalkeeper Alyssa Naeher is the “No. 1 aunty” and loves to babysit. Sophia Smith, who has said she hopes to be a soccer mom one day, is rising in the rankings, too.

“I mean, they had the best role models they could have,” Fawcett says. “They got to hang out with these women every day and see them on the field and go to all the games and see strong women do and compete and work hard and all of it. It’s had a great impact on my girls.”

Adds Morgan, whose 3-year-old daughter Charlie has become a regular at news conferences and in mixed zones: “It’s also important for her to see Mom in a different way and understand that Mom is going to work, Mom is going to her soccer game, and it’s special to be able to take my daughter to work because probably 95 percent of the workforce in general cannot take their kids to work. So if I have the opportunity, I’m going to take advantage of that.

“And I think she’s learned so much from traveling the world with me and being around some of the most confident and powerful women.”

*** *** ***

A few weeks ago, Morgan was asked what Charlie’s plans were for the World Cup. The U.S. co-captain said that they were actually still ironing out details like hotels and travel to games because “it’s still uncharted territory, so we’re trying to break down some barriers that exist. But she’ll be going for most of the tournament.”

Morgan added that Charlie “wants to go swimming all day every day” in Australia and New Zealand, but “I have to break it to her that it’s winter there. That will be a surprise.”

Fawcett and Overbeck are proud to see how players who came after them picked up the maternity fight where they left off and continued to work for more protections and resources for women.

[Who could be the breakout star for this young, talented USWNT squad?]

“I am thrilled to see that it is a little easier, hopefully,” Fawcett says. “To be able to start it, it just makes me feel really good. It was all worth it. All the fighting to get what we needed and all the tiredness and pushing to get through it was worth it to not have to choose and be able to do both. So I’m glad they don’t even have to think about it.”

Adds Overbeck: “I’m happy they were able to watch us and realize their dream could also come and continue being a badass female athlete repping their country at World Cups and Olympics.”

Laken Litman covers college football, college basketball and soccer for FOX Sports. She previously wrote for Sports Illustrated, USA Today and The Indianapolis Star. She is the author of “Strong Like a Woman,” published in spring 2022 to mark the 50th anniversary of Title IX. Follow her on Twitter @LakenLitman.

FIFA WORLD CUP WOMEN trending

Get more from FIFA Women’s World Cup Follow your favorites to get information about games, news and more